VOTERS AREN’T WRONG ABOUT THE ECONOMY — THE STATISTICS ARE

It’s not too late for Harris-Walz to turn this close election into a rout. But they have to align with the economically discontent

Kamala Harris and the Democrats are running on what they claim are the economic successes of Biden’s term. But they’re heading for a trainwreck if they stick with this message. (Being tied with Trump in the polls three weeks out is arguably already a trainwreck.) The statistics they tout—lower inflation, low unemployment, rising wages—don’t correspond to people’s experience, because these statistics have been falsified for decades. Worse, Dems have doubled down on this over the last year, saying in as many words that people don’t appreciate the economic paradise that the Biden Administration has created for them—that people complain too much. That’s a disastrous message, and someone has to fast convince the Harris-Walz campaign to drop it like a hot iron. Moreover, Trump and Vance are running to the left of the Dems on some high-profile economic issues, like Trump’s recent promise to cap credit-card interest rates. That kind of ju-jitsu worked for Trump in 2016, and can work again.

Here are some reasons why Dems have deceived themselves about the state of the economy, and why they need to pivot fast.

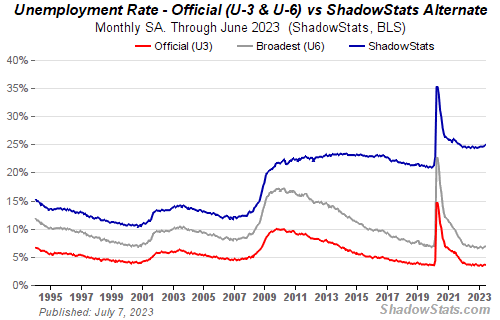

First, people aren’t wrong; the statistics are. The official unemployment numbers are deliberately understated (see for example John Williams, https://www.shadowstats.com/alternate_data/unemployment-charts), and in fact have steadily become more so over the decades since the 1980s. Part-time work is counted as good as full-time, even for people who seek full-time in vain; ‘under-employment’ is hidden. The long-term unemployed who have given up actively looking—because they know there’s no job in their area worth taking—are no longer counted as unemployed, but just removed from both the numerator and denominator. They’re considered out of the labor market. (It would make more sense to count them double rather than not at all, since they’re the hardest part of the caseload and the most disadvantaged.) Jobs with minimal pay, no security, and withered benefits—the gig economy—count the same as what used to be the standard middle-working-class job that could support and house a family.

The unemployment statistics have become fraudulent by means of steady tinkering with definitions, for political purposes. It seems to have started in the Reagan years, when it was very much on the minds of his crew that the economy had undone Jimmy Carter and could easily do the same to Reagan. When, in 1982, unemployment hit 10% for the first time since the Great Depression, Reagan’s approval rating went as low as 42%. So there may well have been a directive, or a spontaneous eager-to-please effort, to jimmy the statistics in his favor.

However this fiddling started, some have reckoned that if unemployment today were calculated in the same way it was in the 1960s and 1970s, it would show Great Depression levels—on the order of 25%. To the comfortable punditry, that seems unbelievable. But voters are certainly acting as if that’s the case.

Next, inflation. Politicians in power have a strong and twofold incentive to understate inflation: rising prices are bad news in themselves, but they also reduce reported economic growth (GDP growth). It’s been a mainstay of national economic accounting since their modern establishment under Franklin Roosevelt that true GDP growth must be net of price increases. Nominal growth minus inflation equals real growth. All politicians in power want to crow about GDP growth; so if they can manage to minimize reported inflation, they’ll have a better GDP growth rate to crow about. Also, investors and financial markets love GDP growth and will usually pump money into stocks when it's reported. Then politicians can further crow about a market boom.

So like unemployment, political interests have corrupted the methods of counting inflation. There’s a lot of opportunity to do so, for example in the choice of what goods and services to count in the ‘basket’ whose prices are tracked.

Seem unlikely that such core, headline government statistics are fiddled? Let’s take some simple evidence. In my youth in the mid-70s, there was a well-known phrase ‘10-cent candy bar’ (like a Snickers or Mars Bar, as distinct from penny candy). How much does a Snickers cost now? Let’s say 75 cents at least. So that’s an increase of 7.5 times or 750% in the 50 years since the mid-70s. But according to the official statistics, total inflation since 1975 has been 600%:

https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm. Try it yourself with any product whose price from a few decades back you clearly remember. It looks like they’re understating inflation by at least a quarter, and therefore also overstating GDP growth.

Inflation is tricky to calculate; no one figure contains the entire truth. Quality changes: for example a cup of coffee costs a lot more than it did in the 70s, but it’s also much better coffee. Same with beer, cars, computers. That’s one reason the CPI is weighted with less changeable commodities like eggs. But it underweights some central expenses like rent and insurance. It’s hard to know whether this is deliberate, i.e. for political purposes. One thing’s for sure, though: if it contradicts people’s experience, it’s political poison to say that inflation is negligible. It’s also economically illiterate plus politically obtuse to crow about bringing inflation down if prices remain high post-inflation: it takes negative inflation to get prices back to what people are used to.

Lastly, housing. The interest-rate rises starting in 2021 to counter inflation (which were misguided, by the way) put house-buying out of reach for many. The unaffordability of housing is also driven by mass private-equity purchases of residential properties. Usually, mortgage interest rates and housing prices move in opposite directions: the higher the rates are, the less principal people can afford to pay, so they bid less. Homebuyers can afford a certain monthly repayment, interest and principal rolled together; so the more interest they have to pay, the less they have to repay principal, meaning less purchase price they can offer. So high interest rates force prices down, unless there’s a concurrent explosion of income. But mass private-equity purchases change this, because the big money is paying cash for residences, unbothered by interest rates. They bid up prices, even as interest rates price many real people out.

This sort of thing is illegal in countries like Switzerland, by the way, where for the most part only real people can buy residential property. Dems in Washington are talking about restricting private-equity property purchases, but, since the Republican-controlled House would block any such measure, the Dems will have to talk about it much louder and make it a stick with which to beat the opposition.

So those are three main economic concerns that are enraging people but that the traditional statistics aren’t capturing. Dems crowing about how good those statistics look only piss people off even more.

This needs saying because even astute (albeit partisan) observers like the estimable Dean Baker continue to advise Harris to tout the economy instead of aligning with the discontented.

What does this portend for November 5? I’m old enough to remember the original “It’s the economy, stupid” election: 1992. The economy had turned sour, maybe very sour. But Bush Sr. didn’t get it, and kept crowing about the Reagan-Bush economic miracle. Voters’ economic sentiments were so strong that Bush got the lowest vote share of any incumbent president in modern history. Do the Dems really want to repeat his arc, from 89% approval rating in the wake of the first Iraq war to 37% of the vote a year and a half later?

What should he have done? When that many people are discontented with the economy, align with the discontented. Never crow about how well the economy’s doing: instead say at most that there are some good signs, but too many people are still struggling and you’ll do whatever it takes to get the economy right for them.

That’s what Harris must do. Moreover, to convince people with specifics, she must promise to: ban mass private-equity buys of residential real estate; attack the extortionate pricing of medications (most visibly insulin); raise the minimum wage; act even more hawkishly on anti-trust measures, clearly blaming price rises on market concentration (i.e. monopolies); reinstate the ban on corporate stock buybacks; and whatever else comes to mind. For the moment, it doesn’t matter so much whether the policies would work or whether they’re the most popular with the most voters. Like FDR experimenting, improvising, throwing everything at the Depression in case something worked, Harris will gain the decisive edge from voters believing she knows the problems are serious and she’s going to try like hell.

POSTSCRIPT: DRILL-DOWN INTO THE 1992 ECONOMY & ELECTION

By 1992 the economy was in recession, but, according to the statistics, not such a severe one, certainly not as bad as 1979-1982. Paul Tsongas, Senator from Massachusetts, was one of the Democratic primary candidates. (I remember thinking “You gotta be kidding—another Greek from Massachusetts?” after Michael Dukakis’ 1988 flop against a very beatable Bush.) I was surprised when Tsongas said, in response to a question about how he would handle the economy, that he would “declare an economic emergency” and take various aggressive actions. I thought that was an over-reaction to what seemed to be an ordinary and overdue recession. But he had put his finger on something, and did better than expected in the primaries as a result. People’s economic experience was worse than the statistics indicated. It’s hard to say why without in-depth research, but one can guess some likely factors. Some jimmying of the statistics was probably already in effect, such that things were worse than they seemed. People had lost a lot of savings in the stock-market crash of 1987. “Downsizing” had entered the language, forcing people to take lesser jobs even if they avoided unemployment. Union membership was down, thanks to Reagan-Bush policies, so workers had less recourse. The deficit was huger than ever—Bush blew past Reagan’s $200 billion deficits and entered $300 billion territory—and yet people saw they weren’t getting much from it. With the Cold War over, they wondered when the peace dividend would hit their bank accounts.

Bush didn’t help himself with his evident cluelessness. Not only did he seem in denial about people’s hard times; his goofy-aristocrat persona—which he could get away with when times were better—became poison when people struggled. His detachment became manifest when he staged a supermarket run, to show what a regular guy he was, and was caught ogling the bar-code scanner at the cash register, a technology that had been around for years, showing how long it had been since he’d been in a supermarket.

Tsongas, who managed for a while to project gravitas despite his lisping delivery and unimposing presence, ran out of gas after some success in early primaries. But Bill Clinton learned from his underdog showing and saw that the general election would turn on the economy. As Bush replayed the culture-war race-baiting tactics that had worked against the hapless Dukakis, Clinton and his attack dog James Carville realized, and hammered it into the campaign staff, that “It’s the economy, stupid.” And that carried him into the White House, while Bush argued in vain that the economy wasn’t so bad.